ANDREAS HOFER (1767-1810) English

by John L. Stoddard, 1903

One of the most enjoyable excursions in the vicinity of Meran leads up the picturesque Passeier Thal toward the broad-shouldered mountain range, known as the Jaufen, the Mons Jovis of the Romans. The drive of about three hours along the northern bank of the Passer not only offers to the tourist a lengthened panorama of delightful scenery, but brings him finally to a precious object of historic interest, the birthplace and home of the famous patriot, Hofer. This hero is to the Tyrolese what Washington is to Americans, and Garibaldi to Italians. Nay, his untimely, tragic end has made him even more beloved, if possible, than they. For Hofer did not live to see the triumph of the cause for which he fought; but perished in the hour of his country's subjugation, having been betrayed by one of his own countrymen, and shot in cold blood by his conquerors. As we drive through the charming valley made illustrious by his birth and battles, the salient points in his career recur to us, and stamp themselves indelibly upon our memories.

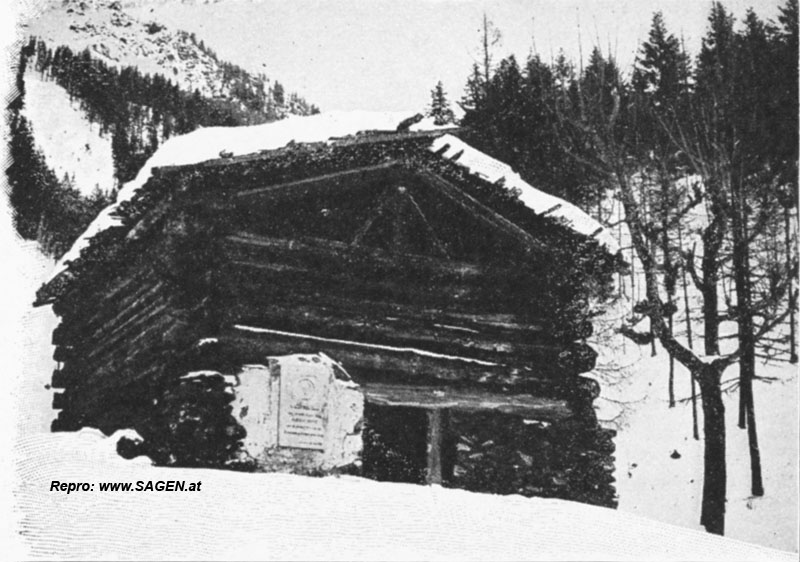

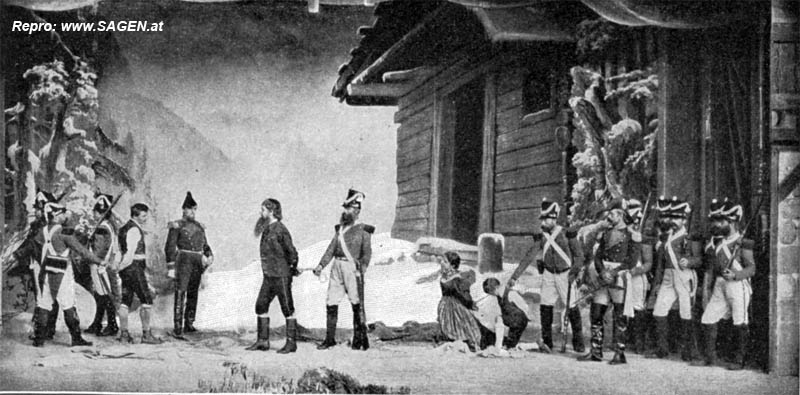

Mountain hut where Andreas Hofer was captured

In 1806, when Bonaparte was tracing with his sword new kingdoms on the map of Europe, he stipulated, as one of the results of his great victory at Austerlitz, that the Tyrol, which for four hundred and fifty years had formed a part of Austria, should be transferred to the possession of his ally, the king of Bavaria. The Tyrolese resented this indignantly. For centuries they had been loyal to the house of Hapsburg; and to be suddenly handed over to the ally of Austria's arch-enemy, Napoleon, seemed to them unbearable. Moreover, their new master, the Bavarian king, showed tactlessness and folly in his mode of governing them. The constitution which had been the groundwork of their national existence was promptly taken from them, and a new series of laws provided in its place. Heavier taxes were levied, and several highly prized religious privileges were withdrawn. Hardest of all, hundreds of young Tyroleans were forced to join the Bavarian army and fight against their former emperor and compatriots, The very name, Tyrol, endeared to them for many generations, was changed, and its use forbidden. Henceforth they were to be known as South Bavarians! Under such circumstances, it was natural that the Tyrolese should plot to rise against their oppressors simultaneously with Austria, whenever the latter felt herself strong enough to make the attempt.

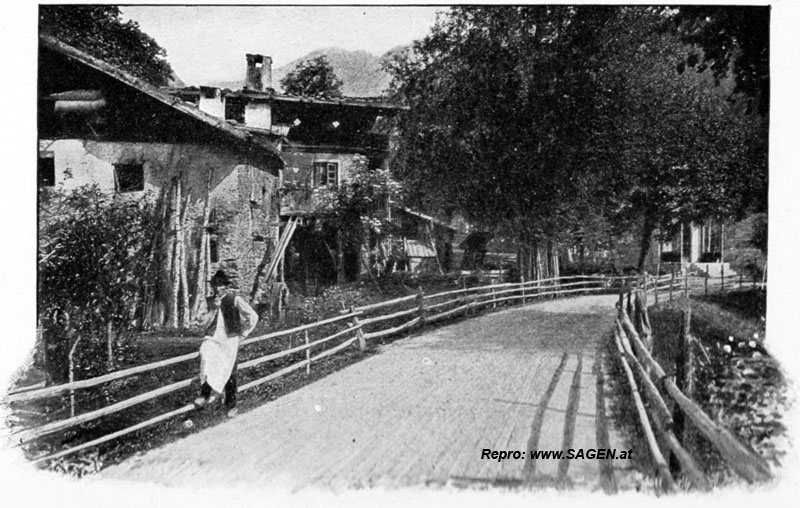

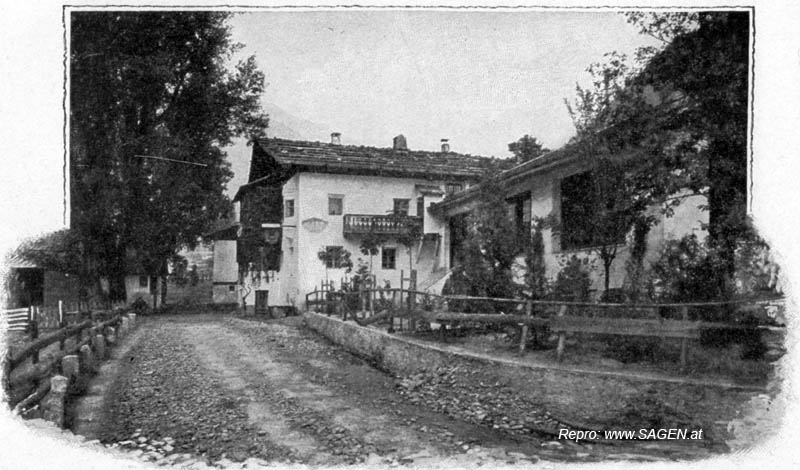

On the way to Hofer's home

Accordingly, in 1809, when war broke out anew between Napoleon and Franz I., the Tyrolese peasants sprang at once to arms. Andreas Hofer was their leader. Nature had molded him for the part he was to play; for to a figure of unusual strength and size were added iron resolution, dauntless courage, a burning love for the Tyrol, and a magnetic eloquence that fired his countrymen to deeds of valor. So carefully had he made his preparations, that when the appointed signal came from Austria, he had but to send out through the land the words: "The time has come!" and everywhere the people rose obedient to his call. The record of what followed forms a thrilling" story, far too long to be narrated fully in these pages. Suffice it to say that Andreas Hofer and his heroes crossed the Jaufen from this valley, attacked the enemy in the mountain passes, defeated them completely, and pushing on to Innsbruck, took possession of the capital. In little more than a week ten thousand of their foes had been destroyed or routed, and their loved fatherland was freed from foreigners.

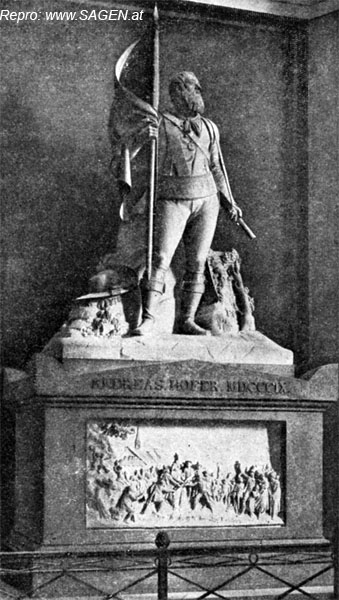

Statue in Hofer's House, in Passeier Thal

But the end was not yet. Napoleon, enraged at this unlooked-for interruption of his plans, dispatched three armies, to enter the Tyrol at different points, and put down the revolt. Against these forces Hofer fought with skill and bravery; winning, especially in the final battle of Innsbruck, a glorious triumph for the Tyrolese. Again his country was delivered, and not one French or Bavarian soldier remained within its borders. Moreover, a few months later, the enemy having returned to the charge, Hofer and eighteen thousand mountaineers defeated the veteran French marshal Lefebvre and twenty-five thousand allied troops.

![The last call to arms [Franz von Defregger]](images/Stoddard_Last_Call.jpg)

The last call to arms [Franz von Defregger]

For the third time the Tyrol was free. The peasant leader now became the ruler of the country. Coins were struck with his effigy, and proclamations were issued in his name. Yet this was not in the least a usurpation. The hero was as loyal as he was powerful; as modest as he was brave. During his governorship, he lived, indeed, in the imperial palace at Innsbruck, but for his personal expenses and salary he drew from the treasury ninety cents a day! His simple habits were the same as when he had been an inn-keeper in the Passeier Thal. He also declared emphatically that he was acting thus solely as the representative of the Austrian kaiser, until the latter should be once more sovereign of the Tyrol. "So, und nit anders" he said.

![The Home-coming of the conquerors [Franz von Defregger]](images/Stoddard_Home_Coming.jpg)

The Home-coming of the conquerors [Franz von Defregger]

At length, however, Napoleon's victory at Wagram and his second occupation of Vienna changed the face of affairs. The defeated Austrian emperor was obliged to sign a treaty, whereby he agreed to withdraw all troops from the Tyrol, and to consent to its reabsorption by Bavaria. When these appalling tidings reached the Tyrolese, they thought them an invention of the enemy. It seemed incredible that, after such fierce fighting, brilliant victories, and loss of precious lives, they must be thrust back into the condition from which they had so nobly freed themselves. Doubt was, however, soon dispelled by the arrival of a messenger from the kaiser, commanding the Tyrolese to make no further resistance, and to resign themselves to the inevitable. Hofer obeyed, and having yielded submission to Napoleon's stepson, Eugene, then viceroy of Italy, ordered his followers to lay down their arms. This many of them refused to do. Hundreds of desperate and unhappy peasants would not accept the situation, and begged their former leader to lead them out once more against the enemy. To influence him to do this, some willfully invented stories of victories of the Austrians over the French. Others reproached him for his cowardice in not completing what he had begun. In an evil moment Hofer yielded to this pressure, which doubtless coincided with his own desires, though not with his calm judgment, and called the Tyrolese again to arms.

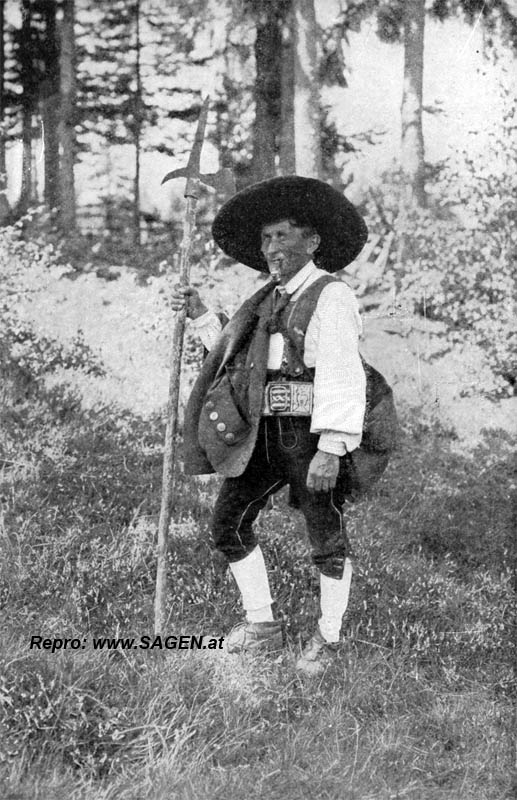

Tyrolese Militia

Fierce fighting followed, especially near Meran and in Passeier Thal; but there was wanting now that national unity which had made all the previous attempts successful, and when another army of fifty thousand French and Bavarians entered the exhausted province, Hofer, unable to resist such overpowering numbers, retired to his mountain home. A price of fifteen hundred gulden was set upon his head, and for this sum a former friend, a man named Riffl, from Schenna, two miles distant from Meran, was base enough to play the role of Judas. Under his guidance a party of French soldiers reached at last the hut where Andreas had taken refuge; and at four o'clock in the morning, on the 28th of January, 1810, the patriot was captured.

One of the heroes of 1809

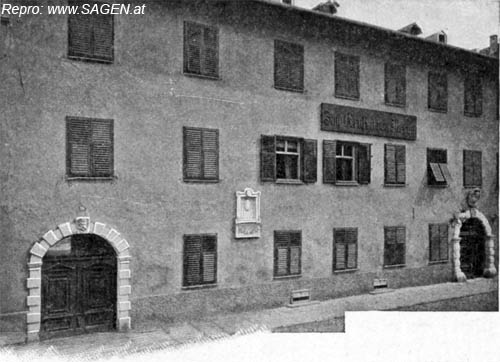

The French troops brought him jubilantly to Meran, where one may still behold the house in which he passed the night before being taken on to Italy. It stands in the street known as the Rennweg, and on its front wall is a marble tablet with the inscription : "In this house, on the night of the twenty-eighth of January, 1810, Andreas Hofer,

the hero of the Tyrol, was detained as a prisoner, before his painful journey to Mantua." A few steps from this structure, on the facade "Graf von Meran," is a marble bust of the great leader, with a memorial tablet testifying to the fact that there, on the same night, he was formally questioned as a prisoner by General Huard.

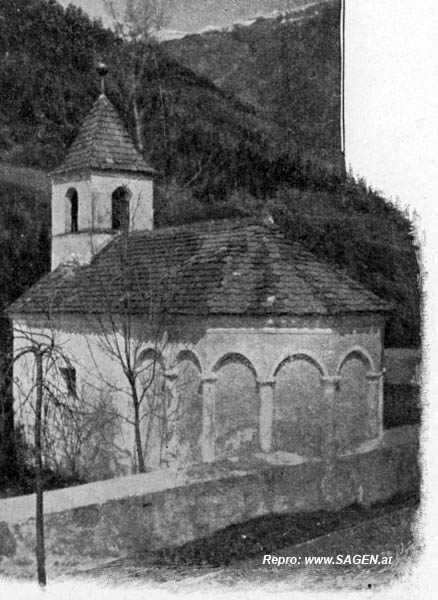

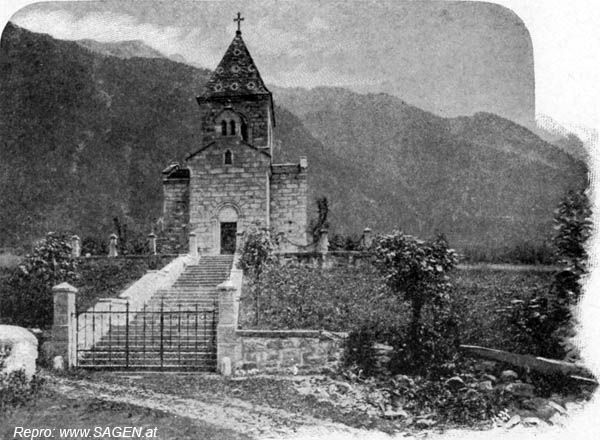

Old chapel near Hofer's house

Andreas Hofer's home

In Mantua, Hofer was promptly tried by court-martial, and sentenced to be shot. He met his fate with the courage which had always characterized him, and when led out to death refused alike to have his eyes bandaged or to kneel. Standing erect before his executioners, his last words were: "Long live Kaiser Franz! Fire!"

Hofer's tomb in the Franciscan Church

New Memorial Chapel, near Hofer's house

Hotel Graf von Meran, with Hofer memorial tablet

Even the printed record of such a life and death is thrilling; but how much more do they impress us, when, after driving through his native valley, we see the modest house in which he lived as child and man! It is still used as a wayside inn, and its rooms arc practically unaltered; while the surrounding mountains wear for us the same calm majesty which clothed them, when he left their snow-clad slopes to give his life for Tyrolese freedom. I looked with mournful interest at many of his personal relics, particularly his hat, threadbare from usage in the field, and pierced with several bullet-holes. But that which touched me most was his last letter, written at Mantua four hours before his death. Among its closing lines are these pathetic words: "Adieu, base world! Death seems to me so easy, that my eyes are not moistened by a tear." In fact, for this brave, simple-hearted man life could have had no more illusions. As he sat, quietly awaiting the inevitable summons, his whole career must have seemed to him a failure. He had fought strenuously, and had gained great victories, but how had they benefited either himself or the Tyrol? He had repeatedly called his countrymen to conflict, but the result of their self-sacrificing efforts had been the second subjugation of their land, whose soil had meantime drunk the blood of thousands of its children. He had toiled only for the good of his compatriots, yet one of them had betrayed him, — and for money! He had lost home, wife, children, and now life itself, to wrest his country from the domination of Napoleon, and to restore it to the Austrian emperor; yet, at the very moment when French soldiers were to shoot him, the bells were ringing in Vienna to announce the coming marriage of that emperor's daughter, Marie Louise, with his conqueror, Napoleon!

Hofer led to execution

Monument to Hofer on Berg Isel

Truly to Andreas Hofer, at that hour, evil must have seemed triumphant. There is something terrible in the sight of such a man, compelled to face the shadow of approaching death, with nothing but a consciousness of rectitude to counteract his sickening sense of personal failure, man's ingratitude, and God's injustice. Sublime indeed must that soul be, which can at such a time look forward confidently to his vindication at the bar of history. In Andreas Hofer's case the vindication came with startling promptness. The marriage bells of Bonaparte were in reality sounding the knell of his stupendous empire. The Tyrol soon became again incorporated with Austria. The traitor Riffl is now execrated as the Tyrolese Iscariot; and the brave martyr of Mantua is the ideal hero of his fatherland.

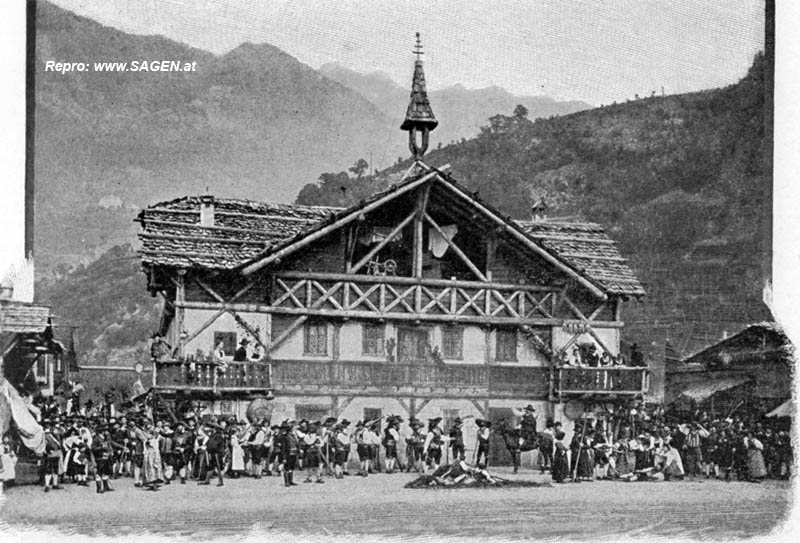

The open-air theatre in Meran

The Austrian kaiser showed his appreciation of his faithful subject by conferring a handsome pension on his widow, and raising his family to the ranks of the nobility. Moreover, in 1823, the patriot's body was brought back to the Tyrol, and buried with impressive ceremonies in the Franciscan church in Innsbruck, only a few feet distant from the splendid tomb of Maximilian I. There, near the figures of illustrious warriors and princes, rises today, in spotless marble, a statue of this whitesouled peasant, whose rare devotion to “God, Kaiser, and Fatherland” has gained for him a deathless fame. But this only one of many proofs of Austria’s reverence for her hero. Thus only a few steps from his home in the Passeier Thal, and close beside the humble church where Hofer prayed, there has been recently built, by subscriptions from the entire empire, a beautiful memorial chapel, adorned with paintings eloquent of his unselfish loyalty and fearless death. Moreover, in the summer of 1893, there was erected on the hill above Innsbruck, called Berg Isel, an imposing bronze statue of the popular leader, marking the spot where he and his companions steadfastly withstood the onslaughts of the enemy, and from which, upon three occasions, he led his mountaineers to as many brilliant victories.

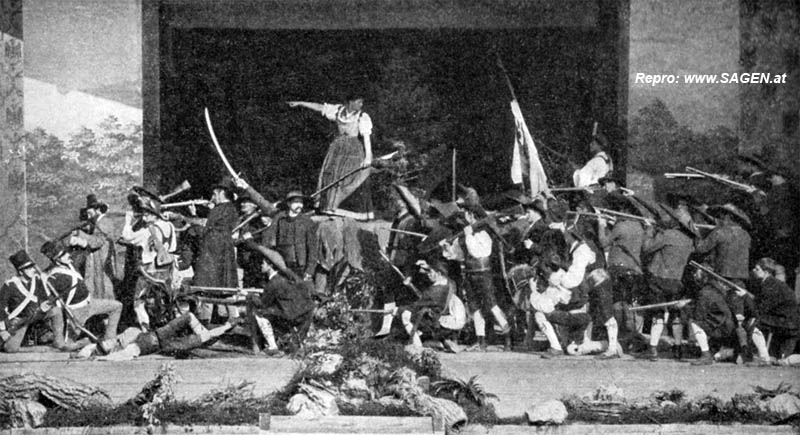

The battle scene in the play "Andreas Hofer"

But that which specially recalls the memory of Hofer to the greatest number of his countrymen, and will perhaps prove more enduring even than bronze, is the portrayal of his life by means of popular plays, of which he is the hero. At Meran, for example, there has been constructed, on a broad meadow, near the town, an open-air theatre, similar to that of Oberammergau, the stage of which represents a village street, before a characteristic peasant's house with pretty wooden galleries and gables. Here, in the spring and autumn, a company of actors chosen from the people performs with admirable skill and genuine enthusiasm two dramas, written by Herr Carl Wolf, a citizen of Meran, which treat of the glorious days of 1809, as dear to Tyrolese hearts as are those of 1776 to Americans. These plays, which are entitled "Andreas Hofer" and "Tyrolese Heroes," produce a profound impression not only on the peasants who behold them, but also on the strangers, who attend them in large numbers. So many are the performers, so lifelike are their tableaux, so passionate is at times their acting, and, above all, so realistic are the movements of the crowds, lit only by the sun and shadowed merely by the passing clouds, that even a foreigner is deeply moved, as he reflects that many of these actors are the grandchildren of the patriots whose deeds they thus commemorate, and that they wear, in many instances, the very clothes which those defenders of their country wore, still kept as priceless heirlooms in their families. Meanwhile, above the background of the rustic stage, tower the same eternal mountains which they saw and loved, their bright green slopes flecked now, as then, with herdsmen's huts and white-walled homes for which the heroes fought and died. At any moment during the performance we have but to lift our eyes, to see, commanding the entire valley, like the presiding genius of the place, the stately form of Schloss Tyrol; and during the representation of the battle we watch the puffs of smoke spring out from the steep mountain sides, and hear the roll of musketry, just as it echoed over the town when the real strife was raging, and when at last the French were beaten back to the precipitous cliffs, over whose brink the mountaineers drove them to their doom.

The hero captured (from the play.)

What could be more instructive and inspiring than national history thus taught? As the play proceeds, one can perceive the lesson gradually stamping itself upon the faces of both auditors and actors; and we are certain that the steadfast men who gather on the stage in answer to the waving of the flag, would rally just as loyally beneath its folds of white and red, if once again the children, playing in the neighboring meadow, should — as they did in 1809 — rush to the town to spread the news that the French soldiers were at hand. These peasants, armed with antique muskets, scythes, and pitchforks, are doubtless just such men as Andreas Hofer led to victory; and the brave, wholesome looking girls who urge their brothers, lovers, and young husbands on to valiant deeds, are capable to-day of no less self-renunciation and enthusiasm. The vines that drape the Küchelberg in graceful terraces have bloomed and ripened into fruit more than a hundred times since the soil from which they spring drank greedily the blood of Austria's invaders; but ruddy as the juice within their purpling clusters still flows the lifeblood of the Tyrolese; and when the curtain of the drama falls, and the impressive strains of Austria's national hymn ring out upon the air, the entire multitude rises reverently to its feet, as is invariably the case whenever that simple but soul-moving composition of Haydn is played. One cannot wonder, therefore, that in the crowd which thus disperses, thrilled with the sentiments awakened by the brilliant page of history that has been unrolled before them, hundreds of loyal lips repeat, in unison with the melody, the words: —

"Gott erhalte, Gott beschütze,

Unsern Kaiser, unser Land!"

The Vintschgau Gate

In driving back into the city, we pass beneath the massive Vintschgau Gate, through which the Paul Revere of the Tyrol galloped to bring the signal of revolt to the expectant people in the western valleys. It is but one of several portals of the old, mediaeval town, one of which, known as the Passeier Thor, is decorated with the favorite emblem of the country, — the eagle of Tyrol, which differs from all other representations of the bird of freedom in being of a brilliant red, surmounting either a silver shield or a battlemented wall. The famous lines referring to it are dear to every Tyrolese heart, and may be thus translated: —

THE RED TYROLEAN EAGLE

Eagle, Tyrolean eagle,

Why are thy plumes so red?

"In part because I rest

On Order's lordly crest;

There share I with the snow

The sunset's crimson glow."Eagle, Tyrolean eagle,

Why are thy plumes so red?

"From drinking of the wine

Of Etschland's peerless vine;

Its juice so redly shines,

That it incarnadines."Eagle. Tyrolean eagle,

Why are thy plumes so red?

"My plumage hath been dyed

In blood my foes supplied;

Oft on my breast hath lain

That deeply purple stain."Eagle, Tyrolean eagle,

Why are thy plumes so red?

"From suns that fiercely shine,

From draughts of ruddy wine,

From blood my foes have shed,—

From these am I so red."

© digital version www.SAGEN.at, Wolfgang Morscher 2009.